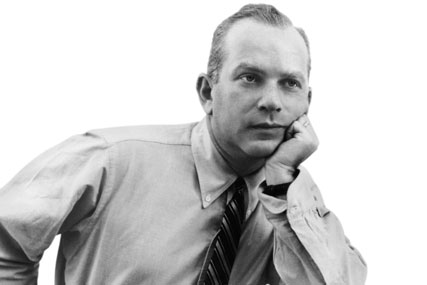

BOB LEVENSON

Former worldwide creative director and chairman of Doyle Dane Bernbach International

Bill Bernbach had the nerve and the wit to hire me in 1959. Some years later, I had the nerve and the wit to hire Bob Kuperman. Neither event made any headlines. Typically, people made headlines when they left Doyle Dane Bernbach, not when they got hired.

What happened in the interim was not magic. We breathed each other's air, celebrated each other's triumphs and wept over each other's failures. (A triumph meant that Bernbach had OK'd an ad, a failure meant that he hadn't.)

Bernbach's disciples learned the lesson. So I wept in David Reider's office and in Helmut Krone's, beamed for Phyllis Robinson and Julian Koenig, and generally felt my way around.

I also got lucky. Volkswagen came my way because I had worked for a few months for a Volkswagen dealer, and because Koenig left the agency and because Reider couldn't get along with Krone. I did El Al because I was born to.

I assaulted people in the halls, begging for work. I loved the business, and DDB people around the world knew it.

And, now, so do you.

By the time I published Bill Bernbach's Book: A History Of The Advertising That Changed The History Of Advertising in 1987, we at DDB had long ago concluded that what happens to society would affect everyone with ever-increasing speed, and that the most powerful force in the world was and would be public opinion, requiring all of us in the communications business to persuade, not sell.

What we learned together at DDB was that the metabolism of the world had changed and would continue to change at a rapid pace, requiring new vehicles to carry ideas to it. Our philosophy was to ally ourselves with great ideas and carry them to the public. We wholly believed that we practiced our craft on behalf of society, and that we must not just believe in what we sell, but that we must sell what we believe in.

I dedicated the book to those who would continue to energetically pursue this kind of vision, who would make the great contributions to our world of communications in the years to come. I am not saying that we predicted the web, but our belief at DDB in the power of persuasion, authenticity and public opinion was ahead of its time, and has certainly proven compatible with how media has evolved in a digital world.

Years ago, I wrote that Bernbach was a visionary with a visionary's zeal. And that he was also a worrier. Most of all, he worried about our doing nothing less than a brilliant job for clients. He believed the best way of winning new business was doing excellent work for the clients already in hand. That is why DDB did not do a new-business presentation for more than 20 years. Yet, he had a knack for dispelling the worries of other people. When Whitney Ruben, the head of Levy's Bakery, fretted about Bernbach's suggestion that the product's name be changed from Levy's Real Rye to Levy's Real Jewish Rye, Bill calmed the waters with the observation: "For God's sake, your name is Levy's. They're not going to mistake you for High Episcopalian." The "You don't have to be Jewish to love Levy's" poster campaign went on to run for many years.

When it came to our most iconic work, Volkswagen, our mantra was always: "The product. The product. Stay with the product." Simple and, ultimately, the manufacturing philosophy and the advertising philosophy were one and the same. The brand spoke with one voice throughout the world and people everywhere recognised that simple and authentic voice.

This was the DDB "shot heard around the world" and it was created by the vibrant people at DDB and Volkswagen of America. In many ways, the brand and the ads were just like us: irreverent, honest and different. A bunch of guys and women (Robinson was the first female copy chief in the business) who were up from the streets of New York - not the streets of Connecticut.

But the most impressive thing about Bernbach was not the specific ads that he inspired, but his creative philosophy that was built on a comprehensive examination of humanity that incorporated genetics, evolution, art, literature and a whole lot more.

When he was presented with the Partner in Science Award by the The Salk Institute, the citation read: "For his penetrating insights into the depths of human behaviour, for his constant refusal to acknowledge the distinction between art and science. For the simple act of giving himself, and, above all, for his help in explaining us to ourselves."

This last clause is extremely important. I once wrote that what Bernbach did was invent the "wheel of persuasion" because he could explain us to ourselves. He could explain us, change minds and perhaps even change men themselves.

That is what DDB means when it says its heritage is one of creativity and humanity, even - at times - creativity for humanity. That, and a whole lot more, is Bernbach's and his agency's legacy.

BOB KUPERMAN

Former president and chief executive of Doyle Dane Bernbach New York

My first meeting (if you could call it that) with Bill Bernbach was in an elevator. He said: "Hello." I mumbled a weak "Hello, Mr Bernbach" in return.

I was 22 years old, fresh out of art school and had been at Doyle Dane Bernbach for one month. It was 1963, and by then most of the first shots of what became known as the "creative revolution" had been fired - mostly by Bernbach and his troops.

Bernbach was leading the agency by roaming the halls and dashing in and out of art directors' and writers' offices, but hadn't yet made it back to where the Young Turks - such as myself - sat, slaving over glue pots and pasting ads together. So this encounter in the elevator terrified me.

After all, this was Bill Bernbach: the Bernbach that everyone in the agency constantly talked about and whose approval was all that mattered to every art director and writer at DDB.

Selling work and winning creative awards paled in the face of being able to say: "We showed the ad to Bill and he liked it."

"Bill liked it" were the three most important words in the world to a creative person.

For a year after, my exposure to Bernbach was limited to the halls, elevators and DDB Christmas party at the Waldorf Astoria.

One day, when I was a junior art director and in one of my rages over an ad that was killed by a client, I announced to the account executive: "I am going to see Bernbach. I've had enough of this client." And before I could stop myself, there I was sitting outside his office, next to his long-time secretary Nancy Underwood, and shaking like a leaf. To my amazement, the man sitting behind the round table spoke to me more like a caring grandfather than like the mythical figure I was in such a nervous state about meeting. He was patient, listened, looked at the ad and gave me some ideas for improvement. Before I knew it, I was back downstairs working on a new ad.

It was like a dream. Did I really just have a meeting with Bernbach? I went storming up there like a self-entitled creative brat and he treated me with respect and kindness. He took the time to listen to a young, egotistical kid from Brooklyn with an accent that made English sound like his second language. He provided me with lifelong inspiration and confidence by telling me that I was one of the young talents in the agency and he was expecting big things from me.

As the years passed, my relationship with Bernbach changed. I became more comfortable in his presence, but it was always clear that he was the teacher and I remained the student. He repeatedly asked me to call him "Bill", and my reply was always the same: "Mr Bernbach, I can't call you anything but Mr Bernbach." He'd laugh and we'd go on with whatever we were talking about.

I discovered things about him that I certainly didn't expect. If you presented to him and he didn't like a particular ad in a campaign, he simply ignored it. He would never address why he didn't like it, or why it didn't work - he just ignored it.

I learned this the hard way in a meeting with Bob Gage. We were showing Bernbach five new ads and I noted that there was one ad that he hadn't said a word about. I did this several times and, on the final try, I received a swift kick under the table from Gage. As we were leaving his office, Gage whispered to me: "If he doesn't talk about it, he doesn't like it." If Bill suggested a line for an ad, it was more than just a suggestion.

I learned little things about him - such as how he was a fastidious dresser and only wore blue shirts because someone once told him he looked best in them, plus they photograph well. On a trip with him to Chicago, I found he, like me, was a "white-knuckle flyer", and that every once in a while he spoke above a whisper. While I still adored him, I started to see that he wasn't perfect. I think this made most of us who worked for him love him even more. He was human and had faults - just like the rest of us.

My relationship with Bernbach became one of the most important in my life. To this day, it's hard for me to talk about him without tears welling up in my eyes.I still have the note he took the time to write to me when I left DDB in 1971. His ideas about the business have been my guiding principles. He pointed out that we are not in the communication business (as many thought then and still think today), but in the persuasion business.

That persuasion is not a science, it's an art.

Research, customer insight and product information may tell us what to say in an ad, but it is how you say it that really matters, and that has never more been true than today.

How you say it takes talent, and figuring out how to say it in the most impactful and effective way takes special talent.

This is what I, and every art director and writer then and now, owe Bernbach.

He made talent count. He made the business one where wit, intelligence and artistry not only mattered but were essential to succeed. He gave us and the world a different view of what we did every day for a living. He called it the "aesthetic choice". Even though I worked for greats such as Carl Ally, Mary Wells and Jay Chiat, I never really stopped working for one man: Bill Bernbach.