He may not have known it at the time but he was indirectly addressing a problem faced by many high profile events this year: how to stop unauthorised live streaming through services like Periscope and Meerkat

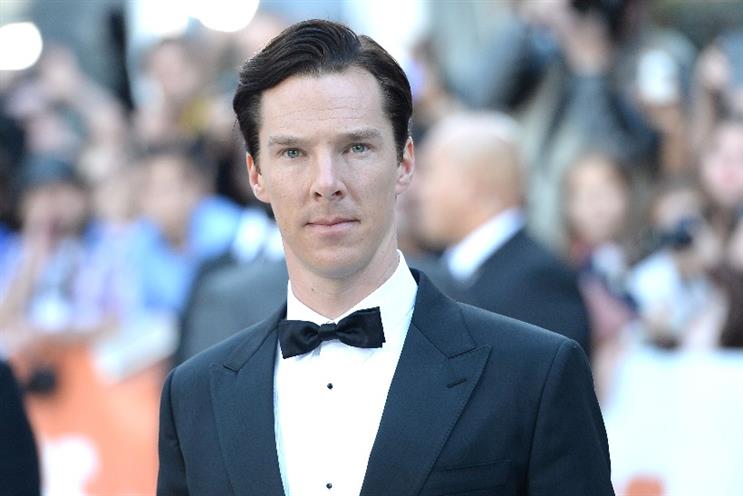

As if Benedict Cumberbatch's performance as Hamlet at London's Barbican had not received sufficient publicity; his recent impassioned plea outside the stage door that theatregoers do not film the performances from within the auditorium has added to the frenzy. His plea leads to much more appealing headlines than "Actor asks audience to stop distracting him on stage and to start respecting intellectual property rights". He referenced the distraction of red filming lights in a dark auditorium rather than the intellectual property angle, but intellectual property rights are also on his side. He may not have known it at the time but he was indirectly addressing a problem faced by many high profile events this year: how to stop unauthorised live streaming through services like Periscope and Meerkat.

Cumberbatch was reinforcing, albeit in a more high profile way, the terms of entry set by the Barbican, who ask: "Please completely switch off and store all mobile devices before you enter the Theatre. Please do not use airplane or silent mode and keep stored until you exit."

There are a number of intellectual property rights in a stage performance of a play such as Hamlet, even though Shakespeare's original text is public domain given the copyright has expired. Any number of these would likely be infringed by filming, recording and/or live streaming them, assuming a big or important enough part is involved:

-

Performers' rights in the actors' performances of the play

-

Performers' rights in musicians' performances in the play

-

Music copyright in John Hopkins's score

-

Dramatic copyright in any choreography

-

Performers' rights in any dancing to the choreography

The audience members who carry out the filming are carrying out the first step in becoming bootleggers; a term one does not hear much these days but which continues to cause problems in, for example, the cinema industry. Being able to prevent the unauthorised recording and/or broadcasting (which includes concurrent internet transmissions) of a live performance by an actor or musician is one of the core intellectual property rights which they have. Even if the audience do not live stream from the auditorium or go on to distribute their recordings as a bootlegger would, just making the recording itself, even for private and non-commercial purposes, is still likely to be a copyright infringement (although perhaps not one that would be actively pursued by the rights holders).

Cumberbatch and the other rights holders involved in this production of Hamlet are in a legally stronger position to stop unauthorised filming and streaming than the organisers of sporting events

Cumberbatch is not alone this summer in asking event attendees to control what they do with their phones: the All England Lawn Tennis Club asked spectators to refrain from using Periscope during Wimbledon – despite the club using the live streaming app itself to capture ‘unique moments' – due to concerns over broadcasting rights.

But Cumberbatch and the other rights holders involved in this production of Hamlet are in a legally stronger position to stop unauthorised filming and streaming than the organisers of sporting events. The difficulty sports events have is that each individual match is not protected by copyright, so copyright cannot be used to stop attendees at matches from filming them. As a result, sports events-owners have to rely on the contract they have with ticket holders, and include in it a ban on streaming or filming from inside the ground. This sort of restriction is perfectly legal though enforcement is harder, particularly against third parties who have access to the content but did not agree to the terms on the ticket. Having said that, if a live stream only appears temporarily on a streaming service, it is unlikely that the usual "notice and takedown" approach would be able to move quickly enough to remove an unauthorised live stream, regardless of the strength of the legal rights relied on. Much better, as Cumberbatch and the Barbican are seeking to do, to try and solve the problem at source by preventing the filming in the first place.

If the audience accedes to his, and the Barbican's, wishes, the only way those not lucky enough to have a ticket will be able to see his performance is to attend a cinema screening or wait for its appearance, if any, on DVD etc. One assumes that that sort of filming is not as distracting for the actors as filming from the third row of the stalls and that the cameramen will have secured the appropriate consents.