Dear Jeremy, I am the marketing director of a major brand, which does not allow me to do any kind of public speaking or build any kind of profile. While I appreciate the ethos behind the mantra ‘let the brand do the talking’, I am concerned this will harm my long-term prospects. What can you advise?

It’s probably best (it nearly always is) to start by trying to understand just why your company imposes these strict limitations on your activities. And I suspect that it’s a combination of two emotions: one fairly respectable and one rather less so.

Celebrity marketing directors are a relatively new breed. They’re famed for their apparent ability to market anything: from pension plans to prophylactics by way of Brix.com and Bristol Zoo.

They see marketing as an entirely portable skill that can be applied to wildly different sectors with the minimum of adjustment.

They spend much more time with their agencies than they do with their retailers and are regularly found at conferences – far more often as speakers (usually keynote speakers) than as mere delegates.

Sooner or later, their chief executives begin to suspect that celebrity marketing directors are at their most committed and most productive when they’re busy marketing themselves. And that, I would guess, is one of the reasons why your own board forbids you from public speaking.

I have some sympathy with them. (I notice, for example, that you regret being unable to "build any kind of profile". Would that be your company’s profile, I wonder – or could it just be yours?).

The less respectable reason is envy. Chairmen and chief executives of major brands don’t like subordinates getting too much credit and becoming more famous than they are.

When the marketing fraternity wonders plaintively why there are so few chief marketing officers on main boards, the answer is often quite simple: it’s much the most telling way for a chief executive to make clear to the world just who’s in charge round here; and, if there’s any credit going, who should get it.

Your salvation lies in the fact that the marketing world is a very small world. If you do a good job, however low your profile, the people who matter will discover who’s doing it. And, suddenly, your absence from platforms and opinion pieces will actually enhance your reputation: a marketing director whose foremost quality is modesty!

You’ll be on everybody’s shortlist. All this, of course, depends on your doing a good job. But that, after all, is what you’re paid to do.

I’m a junior member of staff in a well-established agency. I can’t help but notice how much of the senior leadership is leaving, but we’re not being told that there might be a wider issue. Should I be worried?

Yet again, let me suggest that you stop and think. You say you’re not being told that there might be a wider issue – but just suppose you were?

Suppose you got an all-staff email that read: "Dear all: in the interests of transparency and open management, I’m bringing you up to date with the state of the agency.

"You will have noticed that, over recent weeks, seven senior members of staff have left. These have not been isolated instances but more the result of a shared feeling that the agency was wallowing – and, more specifically, a wider issue that I, as the chief executive, was failing to provide the clarity of purpose and leadership that all seven believed necessary.

"I did my best to persuade them all to stay but failed. As a result, a great many clients are understandably concerned and so I am now dividing my time between trying to reassure them and wondering what to do next. As soon as I’ve thought of something, I will, of course, in the interests of transparency and open management, let you know what it is."

All successful leaders manage to survive periodic hazardous times through the temporary concealment of reality from their troops. It’s an occupational necessity. You need to realise that, being kept in the dark – however unsettling – can be a lot less worse than being faced with the brutal truth without so much as a hint of better times ahead.

Of course you should be worried; just don’t expect to be told why.

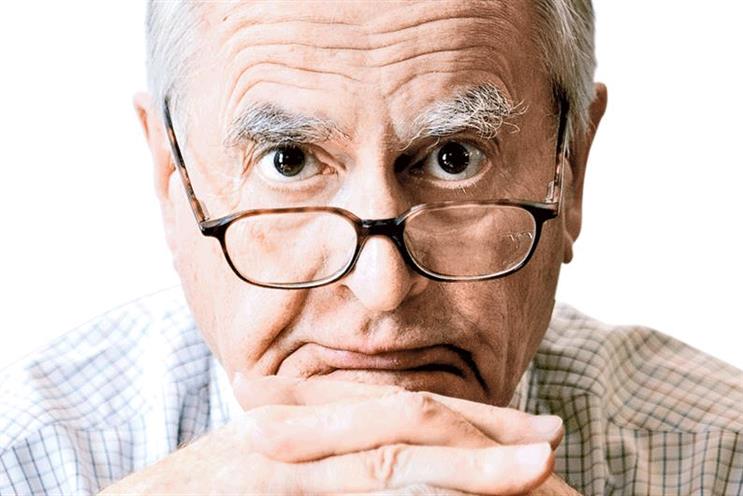

Jeremy Bullmore welcomes questions via campaign@haymarket.com or by tweeting with the hashtag #AskBullmore.