For a state visit, it was not exactly a warm welcome. Last week, Wieden & Kennedy London held a public exhibition at its office on Hanbury Street in response to US president Donald Trump’s visit to the UK. Created by Cuban-American illustrator Edel Rodriguez, the artwork was a bold protest of Trump’s policies, as well as Brexit, environmental destruction and anti-abortion legislation.

The exhibition’s ominous title, Hell is Empty, comes from a line in William Shakespeare’s The Tempest: "Hell is empty and all the devils are here." It is a message that Rodriguez hopes will wake up businesses and consumers alike.

While it might seem unusual for the rebellious Rodriguez, who is known in the US for his anti-Trump art, to choose an ad agency as the setting for his latest show, the artist believes advertising has a powerful role to play in addressing social and political problems.

"Right now, it’s up to advertising and up to companies to stand up to what’s happening; it’s not something to shy away from. You need everybody to shame what’s happening," Rodriguez says. "The language of money seems to be the only language that conservatives understand."

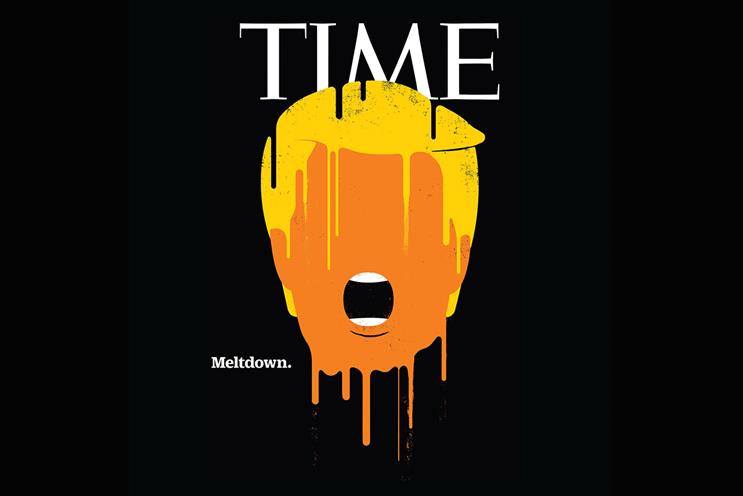

Since Trump rose to power, Rodriguez has been in the spotlight for his controversial illustrations, particularly magazine covers for Time and Der Spiegel, that criticise the political situation in the US. For example, a February 2017 issue of Der Spiegel depicted Trump holding the Statue of Liberty's severed head in one hand and a knife in the other, with the title: "America first."

Last year, Uncommon Creative Studio’s campaign for utility brand Ovo Energy also featured a billboard illustrated by Rodriguez that showed a Trump-like figure facing a giant sun.

Whether for commercial clients or in his personal art, Rodriguez has never shied away from confronting divisive issues. Since emigrating from Cuba aged eight to the US, the artist says he grew up believing: "What we did, leaving Cuba, is not to be wasted. I took it very seriously." Topics such as immigration, identity and politics have influenced him throughout his career.

Rodriguez studied painting in New York, then joined the staff of Time, becoming its youngest art director, at 26, working on the magazine’s Canadian and Latin American editions. His clients have included The New Yorker, Rolling Stone, Fortune, The New York Times and MTV.

In Rodriguez’s commercial work, bridging the gap between his bold point of view and a brand’s message has sometimes proved challenging. "I try to push it, but you don’t always get the freedom," he says. "All this market testing from agencies – I’ve always detested that stuff. The best creativity comes from the gut, not a focus group."

With this conviction, Rodriguez says he asks brands and agencies to involve him early in the process of creating work. "Ad agencies, especially, are losing out by not bringing in artists earlier in the process. You’re going to get ideas you never had."

Rodriguez believes brands must take a stand on controversial issues despite the risk it might pose to their business. He points to examples such as Nike, which last year featured divisive NFL player Colin Kaepernick in its "Dream crazy" campaign.

"Yes, they’re taking a risk. But they’re also gaining credibility, often with a younger generation who are on the right side of an issue," Rodriguez says. "And who will we bank on the future with?"

In a way, the political turmoil in the US has been good for Rodriguez’s career. He says he often gets asked whether the rise of nationalism around the world, as evidenced by Trump and Brexit in the UK, is good for creativity. To that question, he remains defiant.

"World War II was great for inventions. It doesn’t mean we needed World War II and six million Jews to die," Rodriguez says. "Yes, good things can come out of it. People can learn to speak up and be more engaged. Crisis creates things faster, because everyone bands together to confront it. But it’s the result of something very bad."

With his show in London now over, Rodriguez is turning his attention back to crises at home, such as new anti-abortion legislation in some US states. The biggest motivation behind all his work, the thing that keeps him up at night, is political complacency.

"It scares me the most – that complacency is where darkness swoops in," he says. "We try to block things out and keep a happy face, and then my work shows up and goes: ‘Ahh!’ I’m like a visual troll."

.jpg)

.jpeg)