In the ancient Greek myth, Procrustes was a robber and murderer.

He would invite weary travellers to stay the night in his house and use his bed.

While they slept, he would tie them up and then make them fit the bed exactly.

If they were too tall, he would amputate their legs; if they were too short, he would stretch them on the rack.

Either way they eventually died, then he took their money and possessions.

This went on for many years until, eventually, Theseus captured Procrustes.

He forced him to submit to the same treatment and of course it killed him.

Over the centuries the term "Bed of Procrustes" became shorthand for forcing anything, usually ideas or data, into a pre-formed conclusion.

Thinking would be stretched or shortened until it fitted the required answer.

The start point for the investigation wasn’t the information gathered, and then working to discover a conclusion.

The start point was the required conclusion, then working backwards to make all the information fit – anything that didn’t fit being altered or discarded.

The modern equivalent is the saying: "The answer is X, now what’s the question?"

In the case of advertising, it would be: "The answer is ‘brand’, now what’s the question?"

Brand is our Bed of Procrustes, it is so ingrained as an answer we can’t even see it.

And yet several decades ago, brand didn’t exist as an answer.

It was obvious that most of the reasons people bought things were: price, size, range, availability, design, efficiency, durability.

Right at the end of a long list was brand, it was only a small thing, but for marketing types it seemed to be the only part advertising could affect.

As it was the one thing advertising could control, it was exaggerated in importance.

An entire department was built around brand, called the brand planning department.

And it was staffed by university graduates who couldn’t do advertising, but they could write long papers on brand planning.

Which meant clients had to recruit graduates to decipher long papers on brand planning.

And pretty soon university graduates and brand planning took over from advertising.

The answer to every problem had to be cut or stretched until it fitted the solution "brand".

Which meant advertising was reduced to an academic subject, like a thesis.

The answer always had to be brand, there was no other possibility, it had to be made to fit.

But is that always true?

A couple of decades ago, the largest advertising spender in the country was the Central Office of Information.

It had massive accounts like road safety, and fire prevention.

Brand wasn’t the answer to any of its requirements, behavioural change was.

It didn’t matter if anyone found the brand "road safety" attractive, it only mattered whether they drove more safely and didn’t kill so many people.

Another of the biggest spenders was the Health Education Council – it had accounts like anti-smoking.

It didn’t matter whether anyone found the brand "anti smoking" attractive, it only mattered whether they stopped smoking and less people died.

But it seems we’re not interested in changing behaviour anymore, it doesn’t fit with the answer "brand".

So here’s another thought, another way of approaching advertising.

Maybe there’s an alternative to cutting up problems to fit the bed called "brand".

Maybe we could have different size beds to fit different problems.

Just a thought.

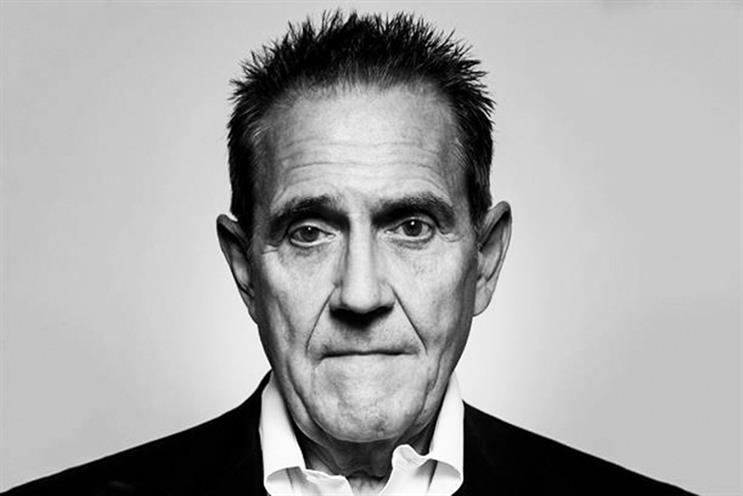

Dave Trott is the author of Creative Blindness and How to Cure It, Creative Mischief, Predatory Thinking and One Plus One Equals Three