If the Black Lives Matter movement has taught us anything this year, it is that to make meaningful change it is no longer good enough to be “not racist”. We need to be “anti-racist”, actively combating racism all of the time.

To do this, we not only need to question our own biases, but also the historical narratives that we have been told. One area of culture where this is particularly important is in sport, which has a long-standing and complicated relationship with race.

Sadly, live sport remains one of the last harbourers of public and overt racial abuse. While progress is being made, it is not being made fast enough.

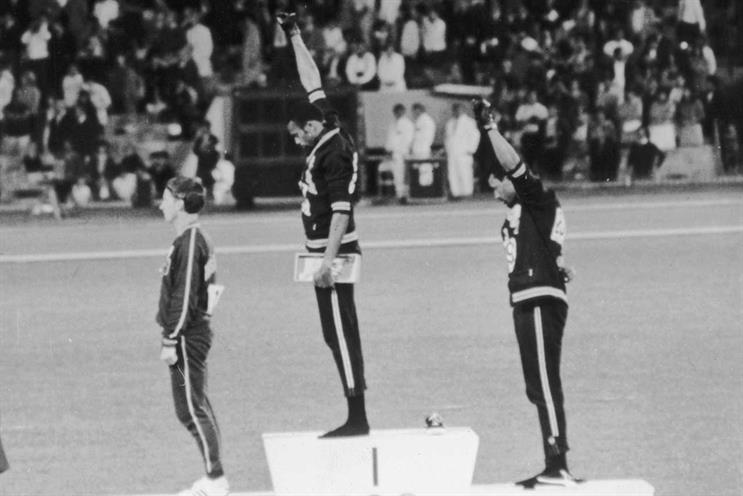

However, on the other side of the coin is sport’s role as a platform for social justice and empowerment. Whether it’s Jesse Owens, Muhammad Ali, Tommie Smith and John Carlos in 1968 (pictured, top) or Colin Kaepernick and LeBron James today, sport has always provided a global stage to combat racial injustice.

Thus, sport and race have ever been intertwined. The best and worst of how we deal with race as a society is exaggerated in sport and this is why it is worthy of examination.

There is another side of race and sport that lies deeper beneath the surface, but is possibly the most damaging of all: sport’s role in forming stereotypes and fuelling myths. The consequences stretch well beyond the pitch, helping to cement and reinforce many of the broader social injustices we face today.

Sport, like so many other constructs in our society, was built on what sociologist Joe Begin calls the “white social frame”. Modern sport as we know it was created at the peak of colonialism. It was in this furnace of injustice that the myth of “the black athlete” was forged.

The idea that black people are naturally more athletic than white may not shock you. In fact, you may have presumed that this was widely accepted as true – such is the power of this narrative that most people at some level do believe in it. But aside from a few hyperlocalised exceptions, no study has ever found any serious evidence to suggest significant athletic differences between races.

How, then, did this myth become so widely accepted? In his book Race, Sport and Politics, Ben Carrington claims that the “black athlete” was not only a conscious “invention” but also a “political entity and [...] an attempt to reduce blackness itself”.

Whether you agree that it was deliberately constructed or not, there is little doubt that the idea that black athletes were physically superior to white emerged in the early 1900s and has been easy to trace throughout the 20th century. Owens’ coach in 1936 claimed: “The n**** excels as it was not long ago that his ability to sprint and jump was a matter of life and death.”

In 1968, commentator Jimmy Snyder got fired for saying live on air: “The black athlete is better to begin with because he has been bred that way.” Even legendary golfer Jack Nicklaus once dismissed the absence of black golfers (pre-Tiger Woods) by saying black athletes “have different muscles that react in different ways”.

If you think this myth has been banished alongside other parts of our unsavoury history, think again. has shown that the way modern commentators talk about white and non-white athletes is markedly different, with comments about athletic ability being more greatly attributed to the latter and intelligence or character to the former.

Similarly, a study by the University of Colorado examining the racial stereotypes of NFL quarterbacks found “that the terms physical strength and natural ability were more associated with black quarterbacks, while leadership and intelligence was more associated with white quarterbacks".

Like so many other dangerous stereotypes, this can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Young black athletes at the earliest level in all team sports are still picked by coaches to play in certain positions to take advantage of their athleticism. Over time, a pattern emerges where black athletes will massively over-index in certain sports or positions, fuelling the stereotype further.

The risk is that, despite all the current goodwill to change, this stereotype stays largely hidden. Former rugby league winger Martin Offiah recently found himself at the centre of a debate on whether the singing of . This is the type of debate that grabs headlines but doesn’t help solve the bigger issue. The part of Offiah’s story we should be focusing on is the role of this myth on his career. When we spoke to him, this is what he had to say:

“I myself suffered from this very same stereotype. As a promising schoolboy centre, I was ushered to the wing in the pro ranks and my 501 career tries are often attributed to my speed rather than my intellect and problem-solving brain […] Fear and change is tough to swallow, especially after a lie was told and believed.”

You may of course argue that this is a relatively harmless stereotype. This is just “sport”, after all. The reality, however, is that it has deep and highly destructive consequences beyond sport.

Perceptions of athletic ability and intelligence are inversely correlated. This is the true destructive force of the myth of the black athlete. Sociologist Harry Edwards, the man who engineered the Black Power protest at the 1968 Olympics, explains: “By asserting that blacks are physically superior… [it creates] an informal acceptance that whites are intellectually superior.” One seemingly positive stereotype leads to another devastating one.

The biases left by this myth run deep. Not just in the fact that coaching and management positions in sport are still vastly controlled by white figures – even in sports that are dominated by black athletes – but more harmfully in the aspirations of young black people who see athleticism as their main route to success.

Advertisers are far from innocent in the creation of this myth. Carrington calls it out specifically, saying the stereotype is “defined by common folklore, sports discourse – most powerfully within the sports media – and by the advertising industries”.

If we are going to help reverse its potency, we need to respond on two levels. On a personal level as fans and spectators, we have to challenge our own biases. We have to question the narratives we’ve been told. We need to look at eight black athletes competing in the 100m final and not explain it as genetic difference, but instead understand the self-fulfilling power of this myth. I can admit from personal experience that, despite being passionate about this cause and open-eyed to the dangers, I still find myself having to regularly battle these biases.

As an industry, we need to do more to avoid any stereotyping of black athletes. We need to resist calling out their “natural” talent. We need to champion their broader achievements and qualities. We need to create campaigns that actively attack this myth and open our eyes to the biases around us. We need to help tell an alternative narrative and help a future generation understand the only differences between us on the pitch and in life are the ones we ourselves have created.

Matt Readman is head of strategy at Dark Horses

Picture: Getty Images