You think your clients behave strangely?

At a meeting with his agency, FCB, some time in the 30s, the Lucky Strike client George Washington Hill chose to demonstrate his theory of advertising by pulling out his false teeth. This was how he amused his granddaughter, he said, and his view was that engaging the public was no different. In Frederic Wakeman’s 1946 novel The Hucksters, Hill becomes the basis for the vulgar Evan L Evans, the fictional head of the Beautee Soap account who, after spitting copiously on the boardroom table, says to an agency meeting: "There – you’ve just seen me do a disgusting thing – but you’ll all remember it."

The book is a wretched tale of immorality (private, public and professional), of contempt and deceit, of greed and double-dealing. When Clark Gable was approached to star in the film of the book, he initially refused it as too revolting a plot for him to be mixed up with.

Wakeman, like the overwhelming majority of writers of novels set in agencies or about agency people, was a copywriter. It’s not difficult to find these books – hardly surprising when advertising as an activity employs an army of writers. What is more surprising is just how bilious and vitriolic so many of them are about the business that warmed and fed them for many years.

Jack Dillon, a copywriter at DDB New York in the glory days of the Creative Revolution, wrote The Advertising Man in 1972 about a senior copywriter on the verge of alcoholism, his marriage in tatters, his job on the line and no feelings for his work and colleagues other than utter contempt. Sloan Wilson’s 1955 The Man In The Gray Flannel Suit tells of a burned-out PR and advertising executive who manages to get off the corrosive treadmill just in time. In the UK in the 30s, Stephen Lister’s gloriously titled Savoy Grill At One tells of an expense-driven and alcohol-fuelled business more interested in golf and bedding others’ wives than achieving anything worthwhile.

Jack Dillon, a copywriter at DDB New York in the glory days of the Creative Revolution, wrote The Advertising Man in 1972 about a senior copywriter on the verge of alcoholism, his marriage in tatters, his job on the line and no feelings for his work and colleagues other than utter contempt. Sloan Wilson’s 1955 The Man In The Gray Flannel Suit tells of a burned-out PR and advertising executive who manages to get off the corrosive treadmill just in time. In the UK in the 30s, Stephen Lister’s gloriously titled Savoy Grill At One tells of an expense-driven and alcohol-fuelled business more interested in golf and bedding others’ wives than achieving anything worthwhile.

Frédéric Beigbeder’s 2001 novel, Was £9.99 Now £6.99, continues the theme in its most toxic form. The presentation of that title on the cover is the cleverest thing about this one-and-a-half-dimensional book (and that may be a bit generous with the dimensions); that and the way in which the manipulation he criticises in the business is practised by him in the book, as in absurd exaggeration, myth disguised as truth and a patina of intelligence – references to Pascal, Houellebecq and Nietzsche do not necessarily make you smart.

The story is of a coke-, money- and porn-obsessed creative director who tries to behave himself out of a job to get the pay-off. The methods he uses include daubing "pigs" in blood on his yoghurt client’s lavatory walls and standing in reception shouting: "Fire me!" Beigbeder claims that the publication of the book achieved dismissal for him, as the executive he ridicules throughout the book was easily identified as his own Danone client. Whether he got the payout is not known and some say he had another job to go to anyway. The plausibility problem is that, in reality, yes, this would get you fired – but thrown out on your arse, without a penny.

What is driving these ad agency authors to state so publicly their loathing of what they do? Is it an inferiority complex, because they feel they are not true writers until they are published poets or novelists or playwrights? Even journalists snub them. But telling people what an asinine business you’re working in doesn’t distance you – it makes you a hypocrite. The only expiation is to get out.

When Clark Gable was approached to star in the film of The Hucksters, he initially refused it as too revolting a plot for him

George Orwell’s 1936 Keep The Aspidistra Flying is full of dismissive contempt for advertising, seen through the eyes of the library clerk Gordon Comstock. He constantly struggles to hold out on ten shillings a week in a damp room in south London trying to be a poet while fighting off the persistent offers of £3 per week from Albion Advertising. Interestingly, although Orwell probably saw him as an idealistic figure, he doesn’t make him particularly sympathetic – he is endlessly self-pitying and sponging off his devoted sister, who can afford it even less than he can. But Orwell at least has a right to his contempt – how could he ever have worked in the business when he once described it as "the rattling of a stick in a bucket of swill"?

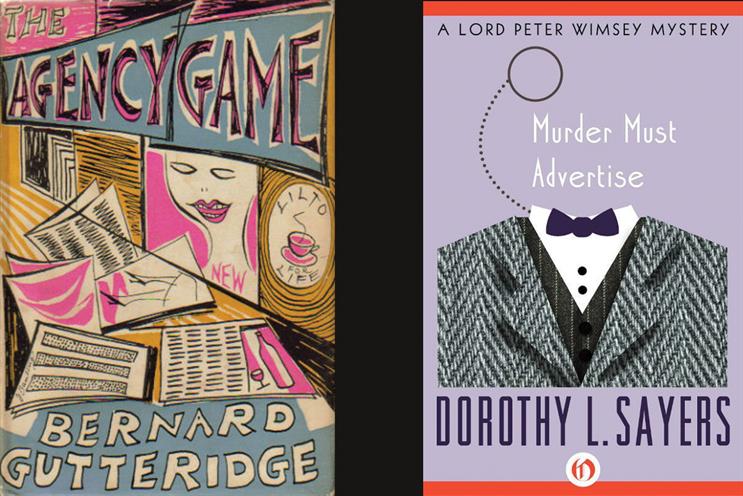

CS Forester, more noted for books involving ships of the line than slick ad agencies, had three advertising executives murder a colleague in his 1930 Plain Murder. And while there’s no outright crime in Bernard Gutteridge’s 1954 The Agency Game, there’s plenty of thoughtful criticism from a pre- and postwar J Walter Thompson insider who became a noted poet.

CS Forester, more noted for books involving ships of the line than slick ad agencies, had three advertising executives murder a colleague in his 1930 Plain Murder. And while there’s no outright crime in Bernard Gutteridge’s 1954 The Agency Game, there’s plenty of thoughtful criticism from a pre- and postwar J Walter Thompson insider who became a noted poet.

It follows a pitch to promote a new bedtime drink – a launch that never happens as the powder is found to contain a powerful aphrodisiac. But the process allows the reader to be taken through every facet of agency activity on and off the premises. It describes prodigious drinking with the first gin and tonic sometimes as early as 10am (it is possibly based on CPV, a Mayfair agency that had not only its own wine cellar but a full-time sommelier), a substantial amount of sex and several beautifully crafted insights into the (usually self-inflicted) flaws in agency practice. He ponders the paranoia of account people, the venality of upper management and the contempt in which marketers can all too easily hold their customers.

Here he is, on what he sees as the warped priorities of creative people, in the mouth of a hard-bitten copy chief: "Your true artist… knows that he has… a twofold duty. First to the people who scan the advertisements he creates. For them he must strive. To educate them and theirs into a pure and correct appreciation of art. All advertising contained within an advertisement must be secondary to this aim."

Their second duty – and this, remember, from more than 60 years ago – was towards peer-group acclamation. There is nothing new.

And Then We Came To The End by Joshua Ferris penetrates the fear, ennui and time-filling in a Chicago agency in the 2000s going through recession. At times almost like Lord Of The Flies with not enough to do, the behaviour gets more and more peculiar. Our central character – who, ambiguously, could be us, the reader – chronicles the way through surrounding scandals, mental breakdowns, an inter-office pregnancy, cutbacks and bizarre briefs, which include: "Make breast cancer funny."

He – we? – survives, but we are uncomfortably unsure why.

One or two novels have been neutral about the business: Dorothy L Sayers, a pre-war copywriter at SH Benson, uses an agency as the background to Murder Must Advertise, where her famous detective, Lord Peter Wimsey, takes a job at Pym’s Publicity to solve a murder on the premises. The murder turns out to be related to a cocaine ring – prescient, perhaps, though not connected to agency life but to the socialite world outside. And Wimsey turns out to be a proficient copywriter, heroically coming up with a campaign the agency rates as one of its best ever.

Agency premises are often ringing with laughter. So why the gloom around the literature? Is it because writers get off on despair?

But advertising should be a brighter stage. It’s a unique junction between business and art, sucking in talent from every quarter and where innovation and originality should be celebrated. As for its people, it’s not that there are inherently more larger-than-life characters; it’s that there’s more permission to be who you are, and agency premises are often ringing with laughter and joyous noise. So why the gloom around the literature? Is it because writers get off on despair more than joy? Is it only the downcast who goes in for the lonely discipline of writing a novel, the others enjoying themselves too much to miss out on the life?

That’s the more affectionate view of John Kenney and Matt Beaumont, both of whom write about the business as we appreciate it – not without criticism but with an enormous dollop of fun. They know there are times when this business is far too ridiculous to take completely seriously. I used to cope by mentally floating up to the ceiling of the meeting room, looking down on myself and asking: "What the hell are you doing?" But they also know that there’s a lot to be said for the massed talent and effort that go into it. It’s not all bad.

Before I’d finished the first chapter of Kenney’s Truth In Advertising, I was sending a copy to my daughter, an agency producer. It’s a belter from the opening paragraphs. His evisceration of those who deserve evisceration – pretentious directors, nodding account handlers, uber-cool creatives and vacillating clients – is as precise as it is funny as it is welcome, and it’s impossible not to recognise people you love and/or loathe.

Before I’d finished the first chapter of Kenney’s Truth In Advertising, I was sending a copy to my daughter, an agency producer. It’s a belter from the opening paragraphs. His evisceration of those who deserve evisceration – pretentious directors, nodding account handlers, uber-cool creatives and vacillating clients – is as precise as it is funny as it is welcome, and it’s impossible not to recognise people you love and/or loathe.

In a New York agency, all leave is cancelled over Christmas – except, of course, for senior management – when an already overloaded group are given a Super Bowl commercial to be written, approved and shot in three weeks. Against an increasingly harrowing and intriguing personal story, the project unravels around our hero, the creative director, when at the pre-production the client calmly announces that the claim around which the entire script has been written cannot be substantiated – and can they make some changes?

Recognise anything?

E, E2 and The E Before Christmas are Beaumont’s agency tales told entirely in e-mails. First published in 2000, it was a radical construct pulled off brilliantly: multiple storylines develop in parallel, utterly believable characters are established only by what they say and what is said about them – in this format, there is little facility for description – and from all these threads arises a magnificent agency structure of chaos, intrigue, hubris, calamity, vanity, sex and unconscious humour. And misunderstanding – particularly misunderstanding. One of my favourite subplots is that of the Helsinki managing director who, through some technical problem no-one can fix, receives every e-mail the short-tempered UK chief executive sends out. Earnest as he is, the Finn responds with ideas to every single one, even if it’s London office carpet tile or coffee-maker issues.

And – to me, anyway – Beaumont aptly demonstrated the truth in the adage: "Revenge is a dish best served cold." Some people assumed enmity between me and Beaumont because I had "let him go" from WCRS 15 years earlier; they therefore assumed that the drug-addled, incompetent and pretentious executive creative director in E must have been a dig at me. In one scene, he is caught with a ladyboy on the boardroom table.

Matthew, that’s a calumny – you know it’s untrue.

It was the broom cupboard.

Andrew Cracknell is a former executive creative director at WCRS and FCB. He is the author of The Real Mad Men