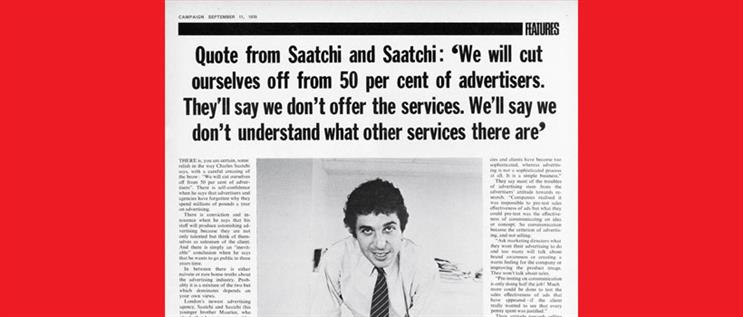

The 1970 interview

There is, you are certain, some relish in the way Charles Saatchi says, with a careful creasing of the brow: āWe will cut ourselves off from 50 per cent of advertisers.ā There is self-confidence when he says that advertisers and agencies have forgotten why they spend millions of pounds a year on advertising.

[Maurice worked at Haymarket, the owner ofĀ ±±¾©Čü³µpk10, but Jeremy Sinclair says Charles had a strong relationship of his own with the editor, Bernard Barnett, āwho was in our offices well in advance ā you [±±¾©Čü³µpk10] knew this [launch] was comingā. Sinclair adds: āYou see from that photo of Charles how young he was [27 years old]. We were all very young. I think that was an important factor.ā]

There is conviction and innocence when he says that his staff will produce astonishing advertising because they are not only talented but think of themselves as salesmen of the client. And there is simply an āinevitableā conclusion when he says that he wants to go public in three yearsā time.

[Charles fulfilled his ambition of floating the company on the stock market ā albeit it took five years as Saatchi & Saatchi merged with Garland-Compton, which was already listed, in 1975.]

In between there is either naivete or rare home-truths about the advertising industry. Probably it is a mixture of the two but which dominates depends on your own views.

London's newest advertising agency, Saatchi and Saatchi (his younger brother Maurice, who pleads that he is two years older than his 24) appear as natural a team as Cramer Saatchi, the creative consultancy that has now folded. But whereas Ross Cramer gave the partnership a much more relaxed atmosphere, the two Saatchis provide a double act of aggressive salesmanship.

Both are excitable, sound very much alike, use the same expressions (most advertising is either āterrificā or āshitā). If one stops talking the other instantly takes up the script. Each is caught up in the infectious enthusiasm of the other. If they become aware that you are accusing them of over-simplification or platitudes, they are sure that you will still accept that what they are saying is true and unique to their thinking.

[Charlesā vision was like a āvirusā, even though āitās an unfortunate analogy at the momentā, David Kershaw says. āWhat it does reflect is a very fundamental attitude ā an outrageous desire to change the world, to do things dramatically, no pussy-footing. It was attracting people who basically say: āFuck it, Iām going to make this change.ā Thatās why I find the article so fascinating. It was the beginningĀ of the petri dish.ā]

What they say is important and not least because of the reputation that Cramer Saatchi built up as a creative consultancy and the work that the members of the new agency have done. But running a creative consultancy, where much of the work may be used for agency new-business presentations that can exist in a marketing vacuum, calls for a different discipline from running an agency.

Many people in the industry, for instance, held the consultancy in high esteem but at the same time wondered how it would succeed in producing ads that must appear in the media.

Charles Saatchi is quick to reply: the consultancy worked for 15 of the top 20 agencies and through them for most major advertisers. He worked, he says, answering another query over his creative image, on many packaged-goods accounts and many of his ads ran in successful campaigns.Ā

The new agency will be heavily orientated towards the creative side and Saatchi believes that the agencyās strongest selling line is the work produced by his people, particularly the two newcomers ā Ron Collins from Doyle Dane Bernbach and Alan Tilby, from Collett Dickenson Pearce.

[āJohn Hegarty and I had the same reaction,ā Sinclair says, recalling reading the interview in 1970. āIt was Charles doing this great interview and all of the philosophy and all the rest of it, we agreed with, but he didnāt mention us and weādĀ made Cramer Saatchi famous. Weād won gold awards, silver awards, weād won at Cannes.ā Instead āhe mentioned these new chapsā and Sinclair thought: āWho are they?ā Half a century later, āmy reaction has not changedā, he says dryly.]

The creative stress, as far as he is concerned, means no lop-sidedness or creative-boutique tag. Like Ronnie Kirkwood setting up his agency a year ago, he says: āWe think of ourselves as a big agency. We are not interested in small clients or small billings.ā In fact, the agency says that it will not accept billings of under Ā£100,000.

āThe creative function is the main one and one of only two services an agency should provide: the other is good media buying.

āThey are the two services neccessary to fulfil the agencyās one function ā to sell the clientās goods. We donāt understand any other services.

āWe will not match the clientās marketing or research departments. If we need research, we will go to top research companies outside. The point about our marketing man is that he is from the retailerās side and so can tell the client what his own marketing department canāt.āĀ

There are also no account executives among the working and control groups and the closer contact between the creative people and the advertiser is designed to make the creative people think of themselves as salesmen.

[Charlesā idea of creatives thinking ālike salesmen of the clientā was persuasive but Bill Muirhead, who joined in 1972, says the agency soon discovered it still needed account executives, like himself, to handle clients and impose business discipline.]

It will be interesting to see whether this is as meaningful in practice as the Saatchi brothers fervently believe and whether, when the agency grows, it will be easy to stop crystallisation of departments and the emergence of account executives. As Maurice Saatchi himself admits: āWe donāt know how the system will work.ā

And his brother: āAll our creative people have to act as if they were salesmen. They have to imagine themselves in the clientās position all the time. They have to see themselves with a warehouse full of the product which has to be sold.

āMost agencies have replaced the basic function of selling with myths and mystiques about marketing and research. But agencies and clients have become too sophisticated, whereas advertising is not a sophisticated process at all. It is a simple business.ā

They say most of the troubles of advertising stem from the advertisersā attitude towards research. āCompanies realised it was impossible to pre-test sales effectiveness of ads but what they could pre-test was the effectiveness of communicating an idea or concept. So communication became the criterion of advertising, and not selling.

āAsk marketing directors what they want their advertising to do and too many will talk about brand awareness of creating a warm feeling for the company or improving the product image. They wonāt talk about sales.

āPre-testing on communication is only doing half the job! Much more could be done to test the sales effectiveness of ads that have appeared ā if the client really wanted to see that every penny spent was justified.ā

Their attitude towards selling they say, coupled with the fact that they wonāt accept accounts under Ā£100,000, will ācut ourselves off from 50 per cent of advertisers. They will say we donāt offer the services. We will say: āWe donāt understand what other services there are.ā But whatever we say, they will never understand us.

āMost advertising is ineffective. Research shows that 75 per cent of Press ads are not even read. And most of these are the work of the big, sophisticated agencies. So they are merely, wasting the clientās money.

[āWe wanted to be the biggest and the best and you see this right through the article,ā Sinclair says. āWhen we started, all the big agencies were crap and all the great agencies were minute. PKL [Papert Koenig Lois] and CDP [Collett Dickenson Pearce] were pretty small in those days and Doyle Dane [Bernbach] was hardly a dot on the map in the UK. All the great work was being done by tiny, little shops. All the big agencies ā McCann, Masius Wynne-Williams, JWT, Benton & Bowles ā were deeply dull. The idea was to be the biggest and the best, to carry on growing until we got worse.ā]

āAn agency boasts if it has increased its clientās share of the market, by say, 18 per cent. Yet the odds are his ad will have been noticed by, say, 10 per cent and read by five. That agency has done a terrible job. Had the ad been any good it would have risen much more.āĀ

Without the motivation of selling, side events like awards become over-important. āGo into any top creative department and tell the copywriter he has put up sales of a product by X per cent, and heāll be pleased. Tell him his ad has won an award and heāll hit the roof with excitement.ā

The setting up of the Saatchi agency comes after two years of refusals by the consultancy to accept various offers of backing to set up shop. In fact, they were offered backing when they left Colletts in 1968 but āwe were not interested in a small business.

āBut now we have reached the stage where we can get the clients and billings we want. Also it was becoming more difficult to work for agencies. We couldnāt agree with them or the way they operated.āĀ

Read the full interview with the M&C Saatchi co-founders here.